Statin medications like Lipitor and Crestor are the new everyday Aspirin. Everyone and their mother is taking them. There are actually serious articles looking at the addition of statins to the public water supply.

These medications play a role in reducing cholesterol. Although, cholesterol isn’t the major player in heart disease we once thought it to be. Statins can reduce the risk of heart disease like heart attack and stroke by 30% regardless of cholesterol levels. They were previously thought to work only by reducing cholesterol, but now are believed to work by reducing inflammation. Despite not knowing exactly how they work, the automatic reflex to prescribe them is getting stronger.

The general guidelines to follow for prescribing statins are:

- People with existing heart disease (CVD), which means any disease that affects blood vessel health, blockage or narrowing

- People with very high LDL (harmful cholesterol) levels

- People above 40 years of age with type 2 diabetes

- People over 40 years of age who have calculated risks* of 7.5% or higher of heart attack or stroke

*Calculated risk is a very important concept. Your current cholesterol level is less important than your risk of having a heart attack. That’s really all that matters as a health outcome. What is the point of lowering your cholesterol if it doesn’t help you? Doctors use different imperfect calculators** called Framingham, ASCVD, Reynolds, or UKPDS – all depending on what information we have available about a patient. We can predict the chance of a future heart attack if we know age, gender, blood pressure, diabetes status, smoking status, cholesterol.

If I calculate your starting risk as a relatively healthy person at 5% it means based on your lab values and other lifestyle factors you have a 5% chance of having a heart attack in the next ten years. In other words, if one hundred people your age had the same lab results you do, FIVE would have a heart attack in the next ten years. I really want to put that in context for you so you understand what this all means in the big picture.

So what happens when we take a statin? On average you can reduce your risk 30% from that original 5% to 3.5%. 30% seems like a big number, but when we put it in context it’s 1.5% individual reduction. On the other hand if you look at someone who has heart disease risks like smoking and diabetes you can increase their starting risk to 20%. Taking a statin for this person on average reduces their chances of a heart attack in the next ten years down to 14%.

Risk doesn’t reduce to zero because no medicine has a one hundred percent risk reduction efficacy. We’re all at some level of risk for heart disease by virtue of being alive and with aging.

**It’s also important to note the risk calculators themselves are flawed and have been shown to overestimate risk by as much as 154%. If someone is calculated to be at a 7.5% risk of a future event, they may in fact be only at a 3% risk and be misguided to medicate.

Certain populations do benefit from taking statins. Others do not. Rather than a blanket approach I find it useful to know who benefits the most and when we should be concerned about side effects that don’t get enough attention from many clinicians. What’s really important to know is that there is a big difference between men and women and between people who have previously had a heart attack or stroke and those who haven’t.

WOMEN

With no previous heart attack or stroke

Women have less risk of heart disease than men. They reach the same levels as men in their 70s – advanced age being the great equalizer. Statins don’t significantly prevent first heart attacks or strokes in women. They don’t seem to save lives in this population.

For women with a 10% risk, taking a statin medication reduces that risk to 7.4%. This can be translated to 9 fewer heart attacks or strokes per 1000 women who took the medication for five years. Some women may find this worth taking the medication while others may not. Confusion exists between studies on which statin medication to use. Certain statins lower cholesterol, but don’t reduce heart disease risk and even increase it in some demographics of women. It also doesn’t seem to matter what the LDL or inflammatory (CRP) starting point is on whether a statin will work. There also isn’t really a point in remeasuring the cholesterol if a woman does decide to take one because the risk reduction is independent of lowered cholesterol levels achieved by the statin.

Recently a woman with diabetes sought my advice for blood sugar control. In 2014 she had been prescribed a medication called hydrochlorothiazide for high blood pressure. According to current common practice she was also given a statin medication to reduce cholesterol and to prevent a future heart attack although she had never had one before. Interestingly, after looking at her previous lab reports her blood sugar levels only increased AFTER being given these prescriptions. Both are known to increase blood sugar. I asked her to stop taking them. She’s no longer diabetic.

According to the WHI (the largest study done on women to date) statins also increase the rate of diabetes in women by 48%.

Other side effects of statins like muscle pain and cataracts do occur. For every 90 women treated with statins 1 will get muscle pain, but maybe not significant enough to stop the drug. For every 140 women taking statins, 1 will develop cataracts. Many doctors don’t give cataracts caused by statins too much importance since cataract surgery is easier to handle than a potential future heart attack. Some women see this differently.

WOMEN

Who have had a heart attack or stroke

Statins provide ~50% less benefit for women that they do for men.

We cannot extrapolate benefit to women who have CVD to those who don’t.

MEN

Who have never had a heart attack or stroke

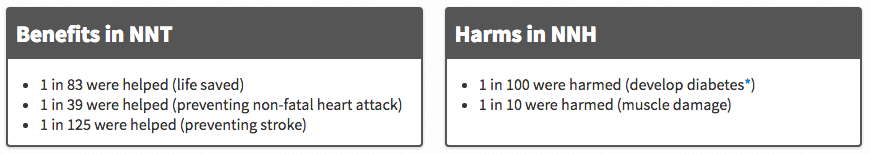

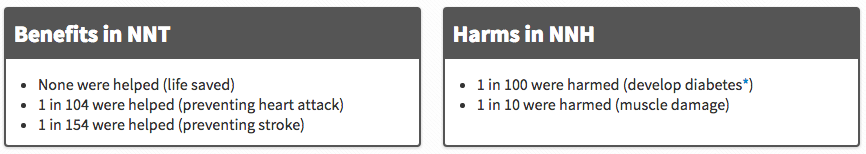

There is a lot more information on men’s benefits and harms related to statin use because men have been studied so much more. In the charts below NNT means the number of people who need to be treated for one person to benefit from the drug. NNH means the number of people who need to be treated for one person to be harmed by the drug.

MEN

Who have had a heart attack or stroke

The ELDERLY

The positive effects for the elderly are less pronounced and the negative effects are unfortunately more pronounced. Statins prolonged the life of patients by 5 to 27 DAYS after taking the medication for five YEARS. Despite this the rates of statin use in the very elderly has gone from 2% to 35% since the 2000s. For those who suffer from heart disease there is a benefit. Those who don’t suffer from heart disease, but have moderate risks for it may benefit. Anyone over 75 should not take it since there is a greater number of people who suffer negative effects like muscle pain (1 for every 77 people) and increasing rates of cancer (up to 22% increased) than there are who benefit from less heart attacks (1 for every 84) and strokes (1 for every 143).

As stated before, cataracts is a problem for this population given for two reasons – age and statins. B.C. residents on statins were 27% more likely to develop cataracts requiring surgery. That means that 20 out of every 1,000 statin users per year were diagnosed with the eye disease and needed operations, compared to 15 per 1,000 people not on the drug.

The YOUNG

People younger than 40 rarely fit the profile for someone who would benefit from a statin. They would have to be a type 2 diabetic who smokes for it to help. In other words, they have to find ways to really increase their risk for the potential reduction from a statin to apply to them.

The RESTLESS

A.k.a those who are anxious about their cholesterol levels

Some people still like to take something to lower their cholesterol even though it likely won’t have an effect on their risk of having a heart attack. It just makes them feel better about it.

There is also a drug called ezetemibe that is used for people intolerant to statins that reduces LDL cholesterol. Unfortunately, it has no effect on future heart attacks or strokes. It may do a good job at reducing cholesterol, but it doesn’t impact the important outcomes at all. Actually, that’s one of the ways the medical community learned that cholesterol is not the only factor in determining someone’s risk of heart disease. Drugs that do a good job lowering cholesterol don’t always do a good job lowering risk. Some people will still go on it knowing it doesn’t have that positive effect overall because it lowers cholesterol.

There isn’t a benefit to take statins short term. You wouldn’t benefit from them in your 50s because you took them in your 30s and 40s. The effect only lasts so long as you are taking them. We also don’t know if the harm that comes from statins – kidney, liver, muscle and pancreas damage isn’t made worse as we age. We just don’t have that kind of data yet or convincing interpretation of the data that does exist.

There are some powerful non-drug approaches to cholesterol reduction and more importantly uncovering why some of us produce more cholesterol than others. One is called the Portfolio Diet (see article here) that in terms of cholesterol reduction almost matches the statins in their efficacy. Diet plays an important role. One of my concerns with patients who take statins, especially younger ones, believe it is a license to eat anything and not change their lifestyle behaviours to reduce their heart disease risk. As one Medscape reviewer put it, “if we’re asking healthy people to take a daily drug forever, we should have the data to back that up. The cholesterol-heart attack link and the achievement of lowered cholesterol without protective effect is an important scientific puzzle.”

Everyone and especially their mother should rethink filling that statin prescription. We need to have in depth shared decision making discussions about the specific risks and benefits for each of us with our healthcare providers.

Women’s Health Initiative (WHI)

Drinking Water & Statins